Here's my favorite part of my systems project. It kinda goes against the positive, generative mood I've been learning to focus on to the exclusion of my usual gloomy self, but I'm really enjoying the thought of it right now. Maybe I'm just overworked and under-slept, or maybe I'm a genius for writing it:

"

The system anticipates that some of those groups may lose interest after a time and stop their maintenance routine, as well as a similar condition on a larger scale, with Beautiful Decay. The system is built with materials and designs which only gain elegance and interest as they are overtaken by nature. While high-tech elements that require power plants at the source and functioning computers on both ends will certainly not continue to function like the Roman Aqueducts which still span many parts of Europe, they can at least retain their composure like the Pyramids in case the society which supports them runs short on resources or moves away, instead of turning to ruins.

"

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Saturday, December 6, 2008

knowing value

I don't remember Pirsig writing about this - he probably thought it was too obvious to state:

Identifying value is, itself, valuable.

This means that just sifting out gold from the dust is a value-creating activity. That's an easy one, as it involves physical motion...

On a subtler level, it also means that just naming the gold and showing somebody else it's there, among the dust, is also a worthwhile contribution to society and the world.

I'm trying to push it, so this may get fuzzy: it also means that just being aware of the fact that there is a qualitative difference between the two substance is a valuable action, a worthwhile skill.

In essence, this is what I'm learning at design school: how to distinguish well-crafted, well-concieved things from those which are not.

....

Identifying value is, itself, valuable.

This means that just sifting out gold from the dust is a value-creating activity. That's an easy one, as it involves physical motion...

On a subtler level, it also means that just naming the gold and showing somebody else it's there, among the dust, is also a worthwhile contribution to society and the world.

I'm trying to push it, so this may get fuzzy: it also means that just being aware of the fact that there is a qualitative difference between the two substance is a valuable action, a worthwhile skill.

In essence, this is what I'm learning at design school: how to distinguish well-crafted, well-concieved things from those which are not.

....

Sunday, November 30, 2008

Thursday, November 27, 2008

what is a tangent?

I was just writing for my systems project and thought about how the future infrastructure system's infinite customizeability will be so dense and so large that people will download "skins" to govern how their lights, solar-panels, water-heater, hydrogen-powered car, nano-bot powered replicator, and other home devices interact with one another and provide comforts to the user.

Once some geek has gone in and tweaked all the millions of settings to get the lights in your house to automatically (and accurately - that's the hard part that requires geekiness) know when you're reading and need bright lights, you'll be able to go to the 'net and download his application.

Once a group of people identify some trendy lifestyle - let's say eco-efficiency just 'cause it's obvious - and define a set of behaviors that the system will follow to help you conserve as much as possible without sacrificing too much comfort, that configuration skin will sweep the nation and you'll know who'se "in" because you'll see their lights turn out just before they leave their house in the morning, instead of the default (just after they leave).

Here's your tangent: If someone defines a set of behaviors that takes that "eco-friendly" one more step to where the user can barely survive, or at least is in constant discomfort, then only people who are too bored (or who have been cowed into accepting the necessity of being soooo eco-efficient) will run those settings. This will effectively become a religion, or at least another medium for religion-y patterns to show themselves in human culture.

Once some geek has gone in and tweaked all the millions of settings to get the lights in your house to automatically (and accurately - that's the hard part that requires geekiness) know when you're reading and need bright lights, you'll be able to go to the 'net and download his application.

Once a group of people identify some trendy lifestyle - let's say eco-efficiency just 'cause it's obvious - and define a set of behaviors that the system will follow to help you conserve as much as possible without sacrificing too much comfort, that configuration skin will sweep the nation and you'll know who'se "in" because you'll see their lights turn out just before they leave their house in the morning, instead of the default (just after they leave).

Here's your tangent: If someone defines a set of behaviors that takes that "eco-friendly" one more step to where the user can barely survive, or at least is in constant discomfort, then only people who are too bored (or who have been cowed into accepting the necessity of being soooo eco-efficient) will run those settings. This will effectively become a religion, or at least another medium for religion-y patterns to show themselves in human culture.

Sunday, November 23, 2008

intersections

I was browsing for sources for the systems project and came across a quote from Neil Gershenfeld of MIT:

...'but "the bubbles kept interfering," Gershenfeld says. "It eventually occurred to us that we should use them." '

(http://www.technologyreview.com/article/18673/)

This "occurred to us" eventually turned into an article published in Science. The same sort of "knowing when to let go of your previous goal and follow the one that has sprung up before you" was described to me by an advisor at UTD, Fred Turner, when we were discussing what I might study if I went there for grad studies.

Perhaps it's a primary function of advisors (of academia in general?) to help relax an individual's pursuit of one particular goal so that he/she may take advantage of those random, tangential discoveries that pop up?

...'but "the bubbles kept interfering," Gershenfeld says. "It eventually occurred to us that we should use them." '

(http://www.technologyreview.com/article/18673/)

This "occurred to us" eventually turned into an article published in Science. The same sort of "knowing when to let go of your previous goal and follow the one that has sprung up before you" was described to me by an advisor at UTD, Fred Turner, when we were discussing what I might study if I went there for grad studies.

Perhaps it's a primary function of advisors (of academia in general?) to help relax an individual's pursuit of one particular goal so that he/she may take advantage of those random, tangential discoveries that pop up?

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

conceptual

Last night I discovered I have no idea what a concept is.

Over the past few years, I've been pushing myself to get comfortable with really difficult, confusing ideas like "close enough to be wrong," which refers to the fact that something has to be somewhat comparable before it really registers as being different. Like an apple and an orange - different, but still fruits. An apple and the ides of march? There's not even a similarity, much less a difference.

But there's a few levels between this and what I thought was implementation. Now I'm struggling to make this sort of profound philosophy into something big but real. Where, exactly, is that border between niggling details and lost-in-the-clouds? I can definitely do both of those, but recognizing which is which and willfully straddling the fence is much more difficult and disciplined.

Over the past few years, I've been pushing myself to get comfortable with really difficult, confusing ideas like "close enough to be wrong," which refers to the fact that something has to be somewhat comparable before it really registers as being different. Like an apple and an orange - different, but still fruits. An apple and the ides of march? There's not even a similarity, much less a difference.

But there's a few levels between this and what I thought was implementation. Now I'm struggling to make this sort of profound philosophy into something big but real. Where, exactly, is that border between niggling details and lost-in-the-clouds? I can definitely do both of those, but recognizing which is which and willfully straddling the fence is much more difficult and disciplined.

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

overwhelmed

Yesterday I was more stressed out than I've ever been because of systems. Today we gave the presentation (the final is in 3 weeks) and I'm taking 20 minutes to relax before I get back to work.

I'm pondering again the nature of information - got a quickie course in library science yesterday and was disheartened and confused (yet again) by the fact that there is far too much information for me to begin to get a handle on it. But i'm still convinced I can find a way around that problem.

Here's another concrete step: somebody at google is trying to get an order-of-magnitude appraisal of how much info is being created:

http://www2.sims.berkeley.edu/research/projects/how-much-info-2003/

I'm pondering again the nature of information - got a quickie course in library science yesterday and was disheartened and confused (yet again) by the fact that there is far too much information for me to begin to get a handle on it. But i'm still convinced I can find a way around that problem.

Here's another concrete step: somebody at google is trying to get an order-of-magnitude appraisal of how much info is being created:

http://www2.sims.berkeley.edu/research/projects/how-much-info-2003/

Friday, November 7, 2008

emergence

This semester's most prominent theme has been about emergence: the formation of order from the interaction of many individual actors.

It was sparked by the book of the same name I read over the summer.

It has been carried on in my classes by the recognition that any successful business phenomenon is fundamentally propelled by lots of individual choices, and never by the imposition of anything on a large group. (though the rules and limitation of choices by what big companies choose to make of course has some effect)

It is repeated in all my sociology study: how does one person's weird clothes become a fashion trend? Why do individual scientists often pursue the same research and make the same discoveries on opposite sides of the world at the same time?

It's especially relevant in my systems class: how can a city (which came about because of the millions of people who chose to move in) act as a unit or a whole and get those people coordinated - without losing the fundamental reality that the city itself is only an abstraction and it's only the individuals who matter?

And it only became clear to me that it's truly an important issue when I was thinking about why all those people started chanting - spontaneously - "yes we can" at Obama's speech earlier this week. Is it possible that a similar impulse - if focused more poignantly in a somewhat smaller group - could cause the spontaneous formation of coordinated dancing like we see in the movies?

At any rate, it's all too little understood and needs to be exploited more effectively.

It was sparked by the book of the same name I read over the summer.

It has been carried on in my classes by the recognition that any successful business phenomenon is fundamentally propelled by lots of individual choices, and never by the imposition of anything on a large group. (though the rules and limitation of choices by what big companies choose to make of course has some effect)

It is repeated in all my sociology study: how does one person's weird clothes become a fashion trend? Why do individual scientists often pursue the same research and make the same discoveries on opposite sides of the world at the same time?

It's especially relevant in my systems class: how can a city (which came about because of the millions of people who chose to move in) act as a unit or a whole and get those people coordinated - without losing the fundamental reality that the city itself is only an abstraction and it's only the individuals who matter?

And it only became clear to me that it's truly an important issue when I was thinking about why all those people started chanting - spontaneously - "yes we can" at Obama's speech earlier this week. Is it possible that a similar impulse - if focused more poignantly in a somewhat smaller group - could cause the spontaneous formation of coordinated dancing like we see in the movies?

At any rate, it's all too little understood and needs to be exploited more effectively.

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

new president

Are we excited by Mr Obama's win? I'm glad he asked, "what will the world be like if our children live for another 100 years?" Because my colleagues and I now have good prospects for jobs as strategic planners.

But more importantly I'm wondering - why did I never watch Bush's speeches so closely, from the beginning to the end, hanging on every word? Why am I so pumped up and excited by Obama's (mostly) empty words and vague promises?

While I have to admit there was plenty he said to admire and that had a starkly different focus than the current president (i.e. it's gonna be hard, we're gonna fail before we win, there are other people in the world we need to think of), his mindset and point of view still don't really square with mine (I would have had him say, "this is a step in the right direction, but it's important to realize that this trip of humanity's into the future will never be over; there are no resting points, and no end goal; tomorrow's another working day and we'd better get some rest.") But the key point is that it makes me feel empowered and energized to hear him say all that, and I know that my work will a little freer and easier in the coming months (until we find out he's as corrupt as a politician) and I'll be a little more daring and outspoken since I feel like our society and our power-structure supports something resembling my point of view.

so the real question becomes, how can I separate this feeling of empowerment from some silly leader? How can I find it in rocks and trees so it won't be endangered by politics? How can I reassure myself that my dreams, ambitions, and goals aren't insane without explicitly having someone tell me so?

But more importantly I'm wondering - why did I never watch Bush's speeches so closely, from the beginning to the end, hanging on every word? Why am I so pumped up and excited by Obama's (mostly) empty words and vague promises?

While I have to admit there was plenty he said to admire and that had a starkly different focus than the current president (i.e. it's gonna be hard, we're gonna fail before we win, there are other people in the world we need to think of), his mindset and point of view still don't really square with mine (I would have had him say, "this is a step in the right direction, but it's important to realize that this trip of humanity's into the future will never be over; there are no resting points, and no end goal; tomorrow's another working day and we'd better get some rest.") But the key point is that it makes me feel empowered and energized to hear him say all that, and I know that my work will a little freer and easier in the coming months (until we find out he's as corrupt as a politician) and I'll be a little more daring and outspoken since I feel like our society and our power-structure supports something resembling my point of view.

so the real question becomes, how can I separate this feeling of empowerment from some silly leader? How can I find it in rocks and trees so it won't be endangered by politics? How can I reassure myself that my dreams, ambitions, and goals aren't insane without explicitly having someone tell me so?

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

physical human factors

Information theory seems - this week - to be the source of all my worries. I learned last week that there is a linear relationship between the number of choices a person has to make a decision between and the time it takes to make that decision (Hick's Law - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hick_law), suggesting both that information can be quantified and that information processing is as rote an operation as assembling toys in a factory.

If this "quantification of information" is as robust as it at first seems, it implies that all information can eventually be broken down in such a way that it can be mathematicized, calculated, and predicted. That would mean that we could begin to get traction on the "information overload" problem, which I think is going to be the defining problem of the coming generation (if it isn't already).

Much more research to be done, but no time to do it. This is partly because I have learned that I only really work under pressure - so I must limit my unproductive dreaming to relatively tangible, immediate things (like drawing and research) if I'm to achieve anything valuable (like schoolwork and grant proposals.)

Sunday, October 5, 2008

Human Computer Interaction

The fundamental limitation of our technologies will eventually be our ability to explain what we want them to do. After nanotechnologies begin to perfect the strength, electro-magnetic distortion, density, and other physical factors of the built environment, and after the continuing Moore's Law growth of processing and storage power lead to greater raw processing power than a human brain(but notably not logical induction), and after Fusion electricity generation is ready for production - i.e. in about 50 years - we will spend most of our time specifying what we want and how to build it.

Probably I'm jaded by my own inability to communicate with people, and I project that difficulty onto computers of the future. It's also possible that my view of what industry will be important is skewed by my own role in the design field. And certainly I'm viewing this all through the lens of the book "What Computers Still Can't Do" by Hubert Dreyfus, as well as my limited experience programming. So I'm willing to admit that there have been huge advances in natural language processing, and that it's common for people to refer to computers that, for example, "think" I want to search for porn when I type in 'put it between your legs and squeeze' and I was trying to look up the thighmaster.

But this Kurtzweilian sense of general optimism concerning the future of computing and of technologies in general - as justified as it all is - obscures a more fine-grained understanding of how and why computers won't fulfill all our dreams any more than television, flying machines, windmills, God, or any other advanced technologies have. Yes, computers can do virtually anything, but they won't just get up and do it.

We'll have to tell them to do it. Yes, we'll have 90% of the human race working several hours a day to do just that, but even so there are certain fundamental limitations on what can be represented with mathematics, logic, and binary notation. Yes, we can asymptotically approach overcoming those limitations as has been happening during the last 50 years of computer science at MIT among other places, but that process is slow and it's likely that our desires and goals will change (partly in response to unexpected, unasked-for functionality like drawing fractals) before we achieve the goals we set out for. Yes, we will eventually be able to build a house by telling the pervasive, hyperconnected global-cloud computer, "Build me a house. [walk inside] I want a wall here [point and wave] and a sink here, with bright windows there that overlook a secluded beach in hawaii, and the windows over there that overlook 5th Avenue in New York City."

But long before then, when those voice recognition technologies are in their infancy, our language will begin to co-evolve in response to them, and our thinking and our ability to describe things will become intertwined with what computer language allows us to describe. Just look at how words (and the associated concepts) like system, network, database, and automatic have colored our conceptions: not just of the built environment (factories, beaurocracies, cities) but of ourselves (social networks, automatic behaviors).

If we want to understand what will be happening 100 years from now, we have to take a specific, in-depth look at how this feed-back cycle could play out, and at least admit that tasks which seem awesome and useful today will be vastly unimportant by then. Not just because they are so easy as to be commonplace, but because new values, standards, and conceptions will define what everyone thinks about when they wake up and what they dream about when they go to sleep. I'm betting they'll be thinking about abstractions - the deeper mathematics necessary to second-guess what the computer will do when it is given complicated, interlocking instructions (the most basic ones left over from today in the assembly language that underlies C++ and other languages) accessed only through vast generalizations that take in millions of objects in one simple sentence like "Bring me a beer" so that we won't have to worry about whether it's going to prioritize that command over keeping the oxygen coming.

Of course, we could program the system to carry out ever more complex tasks. For example, it could respond to the command "Build a house." There's no reason we couldn't have a default size, architectural style, material selection, build time, location, and all the other details built in. But who would want such a house, other than the person who defined that default in the first place? Better to have a system that - when presented with such an assignment - will draw up a menu of options: the number of rooms, colors, layouts, etc. The user can select his or her preferences in increasing levels of detail until they get sick of it and select the "use defaults for further details" option.

While this would make building a house simpler, faster, and more responsive to user needs than even the most skilled architect with a team of assistants can match today, it will none the less require more thought and consideration from your "average user" than he would spend choosing a house today. Anyone who choses will have access to the most awesomely customized built environment they can possibly imagine, but anybody who doesn't have the interest will probably live in conditions not too dissimilar from what we experience today. Even more worrisome, a certain population of people with more curiosity than common sense will use these new technologies to build unthinkably ugly, uncomfortable, and even unsafe environments and objects for themselves. How will we keep these amateurs from polluting our future with nanotechnology mcmansions?

Probably I'm jaded by my own inability to communicate with people, and I project that difficulty onto computers of the future. It's also possible that my view of what industry will be important is skewed by my own role in the design field. And certainly I'm viewing this all through the lens of the book "What Computers Still Can't Do" by Hubert Dreyfus, as well as my limited experience programming. So I'm willing to admit that there have been huge advances in natural language processing, and that it's common for people to refer to computers that, for example, "think" I want to search for porn when I type in 'put it between your legs and squeeze' and I was trying to look up the thighmaster.

But this Kurtzweilian sense of general optimism concerning the future of computing and of technologies in general - as justified as it all is - obscures a more fine-grained understanding of how and why computers won't fulfill all our dreams any more than television, flying machines, windmills, God, or any other advanced technologies have. Yes, computers can do virtually anything, but they won't just get up and do it.

We'll have to tell them to do it. Yes, we'll have 90% of the human race working several hours a day to do just that, but even so there are certain fundamental limitations on what can be represented with mathematics, logic, and binary notation. Yes, we can asymptotically approach overcoming those limitations as has been happening during the last 50 years of computer science at MIT among other places, but that process is slow and it's likely that our desires and goals will change (partly in response to unexpected, unasked-for functionality like drawing fractals) before we achieve the goals we set out for. Yes, we will eventually be able to build a house by telling the pervasive, hyperconnected global-cloud computer, "Build me a house. [walk inside] I want a wall here [point and wave] and a sink here, with bright windows there that overlook a secluded beach in hawaii, and the windows over there that overlook 5th Avenue in New York City."

But long before then, when those voice recognition technologies are in their infancy, our language will begin to co-evolve in response to them, and our thinking and our ability to describe things will become intertwined with what computer language allows us to describe. Just look at how words (and the associated concepts) like system, network, database, and automatic have colored our conceptions: not just of the built environment (factories, beaurocracies, cities) but of ourselves (social networks, automatic behaviors).

If we want to understand what will be happening 100 years from now, we have to take a specific, in-depth look at how this feed-back cycle could play out, and at least admit that tasks which seem awesome and useful today will be vastly unimportant by then. Not just because they are so easy as to be commonplace, but because new values, standards, and conceptions will define what everyone thinks about when they wake up and what they dream about when they go to sleep. I'm betting they'll be thinking about abstractions - the deeper mathematics necessary to second-guess what the computer will do when it is given complicated, interlocking instructions (the most basic ones left over from today in the assembly language that underlies C++ and other languages) accessed only through vast generalizations that take in millions of objects in one simple sentence like "Bring me a beer" so that we won't have to worry about whether it's going to prioritize that command over keeping the oxygen coming.

Of course, we could program the system to carry out ever more complex tasks. For example, it could respond to the command "Build a house." There's no reason we couldn't have a default size, architectural style, material selection, build time, location, and all the other details built in. But who would want such a house, other than the person who defined that default in the first place? Better to have a system that - when presented with such an assignment - will draw up a menu of options: the number of rooms, colors, layouts, etc. The user can select his or her preferences in increasing levels of detail until they get sick of it and select the "use defaults for further details" option.

While this would make building a house simpler, faster, and more responsive to user needs than even the most skilled architect with a team of assistants can match today, it will none the less require more thought and consideration from your "average user" than he would spend choosing a house today. Anyone who choses will have access to the most awesomely customized built environment they can possibly imagine, but anybody who doesn't have the interest will probably live in conditions not too dissimilar from what we experience today. Even more worrisome, a certain population of people with more curiosity than common sense will use these new technologies to build unthinkably ugly, uncomfortable, and even unsafe environments and objects for themselves. How will we keep these amateurs from polluting our future with nanotechnology mcmansions?

Monday, September 22, 2008

http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/taleb08/taleb08_index.html

Nassim Nicholas Taleb writes about the nature of the financial system with a framework similar to the viewpoint I developed while reading about Godel and the philosophy of science a couple years ago. Basically, he says that while logic, science, and statistics tell us many interesting things, it is possible to get a clear perspective on what they don't tell us. Specifically relevant recently, he says that the economists, econometricians, and quants on wall-street have not been paying attention to what they don't know (i.e. Black Swan events, as detailed in his book by that name.)

Much more interesting to me, though, is that he defines the areas where statistics and economic theories correspond with experience as in academia, laboratories, and games:

"First Quadrant: Simple binary decisions, in Mediocristan: Statistics does wonders. These situations are, unfortunately, more common in academia, laboratories, and games than real life—what I call the "ludic fallacy". In other words, these are the situations in casinos, games, dice, and we tend to study them because we are successful in modeling them."

I've been thinking a lot recently about why I don't like poker - I could be good at it if I practiced the statistics and the game theory, but I just don't like sitting around a table thinking deeply about the recursive motivations of "logical" people. Last week I surmised that I'm more interested in those type of people who don't stick to logic, but Taleb gives me a broader way to restate this: I'm more interested in the 99% of reality that takes place outside of groups of humans interacting with each other.

But to tell the truth it's getting kind of lonely out here in reality and I'm daily more convinced I should spend more time learning politics.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb writes about the nature of the financial system with a framework similar to the viewpoint I developed while reading about Godel and the philosophy of science a couple years ago. Basically, he says that while logic, science, and statistics tell us many interesting things, it is possible to get a clear perspective on what they don't tell us. Specifically relevant recently, he says that the economists, econometricians, and quants on wall-street have not been paying attention to what they don't know (i.e. Black Swan events, as detailed in his book by that name.)

Much more interesting to me, though, is that he defines the areas where statistics and economic theories correspond with experience as in academia, laboratories, and games:

"First Quadrant: Simple binary decisions, in Mediocristan: Statistics does wonders. These situations are, unfortunately, more common in academia, laboratories, and games than real life—what I call the "ludic fallacy". In other words, these are the situations in casinos, games, dice, and we tend to study them because we are successful in modeling them."

I've been thinking a lot recently about why I don't like poker - I could be good at it if I practiced the statistics and the game theory, but I just don't like sitting around a table thinking deeply about the recursive motivations of "logical" people. Last week I surmised that I'm more interested in those type of people who don't stick to logic, but Taleb gives me a broader way to restate this: I'm more interested in the 99% of reality that takes place outside of groups of humans interacting with each other.

But to tell the truth it's getting kind of lonely out here in reality and I'm daily more convinced I should spend more time learning politics.

Wednesday, September 3, 2008

Artificial Intelligence

Professor Owen recommended a pretty good book I'm not reading: Engines of Creation by Eric K Drexler.

So much to say about it - hopefully you'll read the systems project and get the gist - but this is the most interesting part: marvin minsky's introduction.

The last few sentences contain a real gem, basically that AI is just the next step in the evolution of mind: awareness, conscious thought, writing, AI. As a tool for us, it will open up exponentially more new avenues than did writing (and writing gave birth to money, literature, and mathematics, before it even started creeping up on computers.)

That ties into a larger idea I've been stewing on how computers fit into the general scheme of human existence... hopefully I'll have the discipline by winter break to turn it into a book before it drives me mad.

So much to say about it - hopefully you'll read the systems project and get the gist - but this is the most interesting part: marvin minsky's introduction.

The last few sentences contain a real gem, basically that AI is just the next step in the evolution of mind: awareness, conscious thought, writing, AI. As a tool for us, it will open up exponentially more new avenues than did writing (and writing gave birth to money, literature, and mathematics, before it even started creeping up on computers.)

That ties into a larger idea I've been stewing on how computers fit into the general scheme of human existence... hopefully I'll have the discipline by winter break to turn it into a book before it drives me mad.

Sunday, August 31, 2008

design futures

I've been reading a report on NASA's "Exploration Technology Development Program," the agency's plan for implementing Bush's ambitious "Vision for Space Exploration." Fundamentally, it says that there isn't enough money to do the job right an on schedule.

But reading into the more subtle details, there are a couple of other interesting weaknesses in the organization that it points out. One is underperforming researchers -of course the majority of NASA's people are highly qualified and do world-class work. But there aren't enough of those for all the work. Also the report indicates that the program isn't paying enough attention to nuclear propulsion for getting to the moon and to mars. I had no idea this was even an efficient way to get there!

But there are two other aspects that are really relevant to designers: one is that the report concludes that none of the research groups is doing a good job considering human factors. This is one of the historical strengths of industrial design and is a huge area of current growth - I think it represents the best opportunity for designers to get into the space exploration business. Second is that the report indicates widespread - but not quite endemic - lack of systematic planning and coordination across NASA projects, and to a greater degree among all government research projects, as well as with the private sector. I don't know if those scientists and engineers would like a non-specialist coming up with the bigger picture, but it seems like a perfect fit to me.

But reading into the more subtle details, there are a couple of other interesting weaknesses in the organization that it points out. One is underperforming researchers -of course the majority of NASA's people are highly qualified and do world-class work. But there aren't enough of those for all the work. Also the report indicates that the program isn't paying enough attention to nuclear propulsion for getting to the moon and to mars. I had no idea this was even an efficient way to get there!

But there are two other aspects that are really relevant to designers: one is that the report concludes that none of the research groups is doing a good job considering human factors. This is one of the historical strengths of industrial design and is a huge area of current growth - I think it represents the best opportunity for designers to get into the space exploration business. Second is that the report indicates widespread - but not quite endemic - lack of systematic planning and coordination across NASA projects, and to a greater degree among all government research projects, as well as with the private sector. I don't know if those scientists and engineers would like a non-specialist coming up with the bigger picture, but it seems like a perfect fit to me.

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

singularity

I saw in the NYT today a thought-provoking article about Verner Vinge (a sci-fi writer) and Ray Kurtzweil. They both write dramatic stories about computers taking over.

I love sci-fi and I'm delighted these guys are writing books that get people thinking about the future. But I totally disagree with their underlying assumptions. Without getting to far into all the details of how and why the specifics of their arguments are far out and unlikely, I'll skip straight to the philosophical reason they're wrong:

Computers are fundamentally different from humans and don't compete with us for resources. They depend on us, not just in the short term to feed them electricity and repair them, but also in the long term to tell them what to do and let them evolve.

A reader of the article summed up the basis of what I have felt a little more poetically than I can, so I'll quote her:

"

The simple reason we don’t have anything to worry about regarding computers out thinking us is that they don’t need to and never will. What I mean by this is that *we* think because we need to to survive. Computers will never think because they don’t need to survive - they cannot ever care if they are switched off. We can ‘lend’ them biological imperatives but we cannot produce life and *that* is the big mystery that trumps consciousness and thought.

— Marie

"

I've got a book on this subject brewing in the back of my head but I don't know whether it will be more profitable to publish a short-ish article about it now or to wait and give a fully-formed thesis on it in about 5 years.

I love sci-fi and I'm delighted these guys are writing books that get people thinking about the future. But I totally disagree with their underlying assumptions. Without getting to far into all the details of how and why the specifics of their arguments are far out and unlikely, I'll skip straight to the philosophical reason they're wrong:

Computers are fundamentally different from humans and don't compete with us for resources. They depend on us, not just in the short term to feed them electricity and repair them, but also in the long term to tell them what to do and let them evolve.

A reader of the article summed up the basis of what I have felt a little more poetically than I can, so I'll quote her:

"

The simple reason we don’t have anything to worry about regarding computers out thinking us is that they don’t need to and never will. What I mean by this is that *we* think because we need to to survive. Computers will never think because they don’t need to survive - they cannot ever care if they are switched off. We can ‘lend’ them biological imperatives but we cannot produce life and *that* is the big mystery that trumps consciousness and thought.

— Marie

"

I've got a book on this subject brewing in the back of my head but I don't know whether it will be more profitable to publish a short-ish article about it now or to wait and give a fully-formed thesis on it in about 5 years.

Sunday, August 24, 2008

green architecture

I ran a research project this summer focusing on the use of remote collaboration technologies (like phone and email) among young architects. I learned that one of them is building a water-neutral building in Seattle. This means it will reuse all of its gray- and black-water - there's no need to connect it to the public mains or sewer.

He mentioned it in passing as we were looking at photos of him giving a seminar on how to overcome all the different regulatory hurdles to accomplishing this. I'm amazed it's possible, but even more amazed it hasn't been splashed all over the design-world press.

I can't wait to get more specifics and copy it!

He mentioned it in passing as we were looking at photos of him giving a seminar on how to overcome all the different regulatory hurdles to accomplishing this. I'm amazed it's possible, but even more amazed it hasn't been splashed all over the design-world press.

I can't wait to get more specifics and copy it!

Monday, August 18, 2008

Focus

I have thousands of compelling ideas - a dozen or more I'm sure would make a fulfilling life's work for me. I want to be able to choose one and stick with it for the couple of decades it will take to get me tenure at a good university in a warm climate. This may require honing my intuition to pluck the right one out of the air like a fly, or building up a logical framework to reveal the optimal choice, but even if it's just repeated blows to the head until I can only remember one option I'll have achieved the goal.

Sunday, August 17, 2008

new language

School starts tomorrow but I just installed Maya and I want to stay up all night playing with it. Maybe if I go to sleep now this tonsil infection will go away before there's any real work to be done?

Tuesday, August 12, 2008

Monday, July 14, 2008

planning

There will be another earthquake in San Francisco. There will be more hurricanes or tsunami in Florida, Indonesia, and Mexico. There will be more flooding along the Mississippi. Obviously these will be disasters - but more importantly they will be opportunities. They will be a (relatively) blank slate to build new buildings, restructure cities, and possibly build new governmental entities.

Is anyone planning for these eventualities and gearing up to take the best advantage of them?

Is anyone planning for these eventualities and gearing up to take the best advantage of them?

Friday, May 30, 2008

neuroimaging as the new alchemy

http://www.wired.com/medtech/health/magazine/16-06/mf_neurohacks

This article presents a refreshingly skeptical view of recent brain imaging science, but I think it doesn't go far enough to indict much of what's called "science" in our culture today.

While all sciences were little more than vague insights and philosophical speculation at one point, it's clear that mathematics, chemistry, and physics, have moved beyond con-games and become realities in their own right - dogmas shared by large groups of people who may well never realize that other people don't see the world the way they do. (Did you know some people neither know about nor believe in integrals, quazars, valence bonds, or heaven?)

Never the less, I support the softer sciences, like social sciences and economics, brain sciences, psychology. They have the potential to traverse the same path as the hard sciences by eventually achieving some amazing, powerful, and mysterious description of the world. When they can suck in believers by the thousands with a brief, intense flash of epiphany, they will be productive outlets for some of the insanity and eccentricity that the process of evolution has bred into us.

This article presents a refreshingly skeptical view of recent brain imaging science, but I think it doesn't go far enough to indict much of what's called "science" in our culture today.

While all sciences were little more than vague insights and philosophical speculation at one point, it's clear that mathematics, chemistry, and physics, have moved beyond con-games and become realities in their own right - dogmas shared by large groups of people who may well never realize that other people don't see the world the way they do. (Did you know some people neither know about nor believe in integrals, quazars, valence bonds, or heaven?)

Never the less, I support the softer sciences, like social sciences and economics, brain sciences, psychology. They have the potential to traverse the same path as the hard sciences by eventually achieving some amazing, powerful, and mysterious description of the world. When they can suck in believers by the thousands with a brief, intense flash of epiphany, they will be productive outlets for some of the insanity and eccentricity that the process of evolution has bred into us.

Saturday, May 24, 2008

On religion...

Imagine a world in which generations of human beings come to believe that

certain films were made by God or that specific software was coded by him.

Imagine a future in which millions of our descendants murder each other

over rival interpretations of Star Wars or Windows 98. Could anything --

anything -- be more ridiculous? And yet, this would be no more ridiculous

than the world we are living in. -Sam Harris, author (1967- )

(thanks to Word A Day for sending the quote)

certain films were made by God or that specific software was coded by him.

Imagine a future in which millions of our descendants murder each other

over rival interpretations of Star Wars or Windows 98. Could anything --

anything -- be more ridiculous? And yet, this would be no more ridiculous

than the world we are living in. -Sam Harris, author (1967- )

(thanks to Word A Day for sending the quote)

Saturday, May 17, 2008

design as hypnosis

The fundamental focus of the academic program here at ID is communication. Using numbers, words, and pictures to convey ideas to other humans happens at the intersection of graphic design, marketing, business thinking, and - of course - art. Is it exaggerating to say that communication is the central activity of every human organization?

I've been learning to make foam-core models, posters, books, movies, sound clips, and photos all towards the end of showing somebody what I'm talking about. At least half of the genius behind any idea is how well it's represented and how convincingly it is presented. Whereas the struggle of an artist is to represent something exactly and precisely as he sees it, the struggle of a designer is to get somebody else - or better yet a large group of people - to see what he sees, whether or not that requires actually building a detailed, precise instantiation.

The logical conclusion of this conception of design is that the ideal designer can induce mass hallucinations.

The best place to learn about hallucinations is religion, though there are important things to learn from theater and magic as well.

1) Set aside a meeting time regular intervals, a few days apart so that the message we're repeating gets rejuvenated just as it's about to be forgotten.

2) Bring a bunch of people together physically, and use some passionate rhetoric, interpersonal drama, or other means to bind them emotionally so they'll all trust each other and feel as a community.

3) After a few weeks of meetings, have an extra-long meeting - maybe two days straight? - and pump up the energy and the abstraction of the message so that not everybody is quite following and they're struggling to imagine what you might be getting at.

4) Once everybody is out in dream-land, jump back down to a more concrete level and give a few specifics (but not as finalized or closed as a model, more like just a few attributes) so they will all be able to agree on something when discussing later.

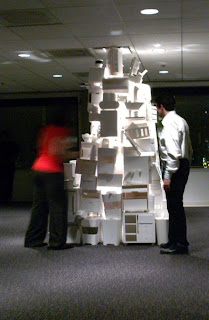

(photos from last night's end of year show)

Tuesday, May 6, 2008

intelligence

From the new york times today:

As is said of biologists earlier in this article, I've often asked myself why humans are so damn intelligent. This gives the most poignant answer I've seen so far: not to outsmart the environment so much as to outsmart each other.

The benefits of learning must have been enormous for evolution to have overcome those costs, Dr. Kawecki argues. For many animals, learning mainly offers a benefit in finding food or a mate. But humans also live in complex societies where learning has benefits, as well.

“If you’re using your intelligence to outsmart your group, then there’s an arms race,” Dr. Kawecki said. “So there’s no absolute optimal level. You just have to be smarter than the others.”

As is said of biologists earlier in this article, I've often asked myself why humans are so damn intelligent. This gives the most poignant answer I've seen so far: not to outsmart the environment so much as to outsmart each other.

Thursday, April 24, 2008

“We should fight with better governance and better intelligence. We have to empower communities to better defend themselves, not with weapons but with organization.”

A quote from Jelani Popal, working on development for the government of Afghanistan, in reference to overcoming the Taliban there. From the New York Times:

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/24/world/asia/24afghan.html?pagewanted=1&hp

Mr. Popal has found a succinct way to sum up the implications of the reading and thinking I've been doing on the subject of politics for the past few years. Not just on the small scale - as when fighting a particular group in a particular place - but in the global, historical quest to have our own children and nation overcome those who would stand in our way: we have to be more efficient and productive, not more destructive.

Now the question is: what is the role of science and technology in this struggle to organize, seeing how it was born from the pursuit of ever larger and more effective killing machines?

A quote from Jelani Popal, working on development for the government of Afghanistan, in reference to overcoming the Taliban there. From the New York Times:

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/24/world/asia/24afghan.html?pagewanted=1&hp

Mr. Popal has found a succinct way to sum up the implications of the reading and thinking I've been doing on the subject of politics for the past few years. Not just on the small scale - as when fighting a particular group in a particular place - but in the global, historical quest to have our own children and nation overcome those who would stand in our way: we have to be more efficient and productive, not more destructive.

Now the question is: what is the role of science and technology in this struggle to organize, seeing how it was born from the pursuit of ever larger and more effective killing machines?

Saturday, April 5, 2008

Evolving politics

An article in the NYT today said that Shell Oil sponsored the screening of an independent documentary about the failure of plans to build several new coal-fired power plants in Texas.

Shell supported the event, said its president, John Hofmeister, “because we felt it was an appropriate venue to share and discuss our commitment to developing technologies, such as coal gasification, and other responsible energy solutions.”

This is weird - as the NYT reporter pointed out. The fact that the head of a giant oil company would support a: an independent documentary, b: one that is all about the failure of the political model of the whole industry, and c: a group, message, and activist explicitly against the environmental impact of their business model, surprised the people screening the film, he reported.

Now my own thoughts on the subject: the fact that a man who controls billions of dollars of profits doesn't have all these protesters shot is a testament to the success of our open yet structured society. The fact that the protesters used media to win the fight against huge profits by huge companies (the subject of their movie and of the article) is testament to the power of communication, especially the internet. The fact that the CEO of Shell found out about all this, and heard enough about it to understand the protesters' motivations, is a demonstration that the free flow of information can change the way that the power structure leads to bad decisions, conflict, and destruction of life.

The possibility of hearing what's happening far away - think of a newspaper in 1800 - leads to cross-pollination of ideas. But the internet allows a much deeper transfer of information: not just a few hundred words, but sharing experiences to an unlimited depth of personal recounting. Rather than just learning what the enemy is up to, it's now possible to get deep enough in that enemy's headspace to see where your interests overlap and to allow a recognition that we all want the same things from this world.

On the other hand, Rick Perry apparently doesn't take the time to be informed about all the other people and how they live and think, and thus tries to do things we consider stupid like building 11 brand new coal-fired plants. So clearly we still need more than communication to build utopia.

Shell supported the event, said its president, John Hofmeister, “because we felt it was an appropriate venue to share and discuss our commitment to developing technologies, such as coal gasification, and other responsible energy solutions.”

This is weird - as the NYT reporter pointed out. The fact that the head of a giant oil company would support a: an independent documentary, b: one that is all about the failure of the political model of the whole industry, and c: a group, message, and activist explicitly against the environmental impact of their business model, surprised the people screening the film, he reported.

Now my own thoughts on the subject: the fact that a man who controls billions of dollars of profits doesn't have all these protesters shot is a testament to the success of our open yet structured society. The fact that the protesters used media to win the fight against huge profits by huge companies (the subject of their movie and of the article) is testament to the power of communication, especially the internet. The fact that the CEO of Shell found out about all this, and heard enough about it to understand the protesters' motivations, is a demonstration that the free flow of information can change the way that the power structure leads to bad decisions, conflict, and destruction of life.

The possibility of hearing what's happening far away - think of a newspaper in 1800 - leads to cross-pollination of ideas. But the internet allows a much deeper transfer of information: not just a few hundred words, but sharing experiences to an unlimited depth of personal recounting. Rather than just learning what the enemy is up to, it's now possible to get deep enough in that enemy's headspace to see where your interests overlap and to allow a recognition that we all want the same things from this world.

On the other hand, Rick Perry apparently doesn't take the time to be informed about all the other people and how they live and think, and thus tries to do things we consider stupid like building 11 brand new coal-fired plants. So clearly we still need more than communication to build utopia.

Saturday, March 29, 2008

Monday, March 24, 2008

Miranda July

I was completely freaked out the first time I heard a recording by Miranda July ten years ago, and promised myself I'd never subject myself to any of her work again - but since then it seems she's mellowed.

Check out this video where she demonstrates the industrial production process of making buttons:

http://www.vbs.tv/video.php?id=1454975012

After seeing this and falling in love with her, I went to her website and found out that she is way too accomplished and productive to pay attention to me. But that's good - it means I can analyze without fear of finding out I didn't do enough research and am completely wrong.

Beyond her excellent production values, notice that she presents within an altered reality, which she unabashedly creates with arbitrary ignorance of object permanence, the impersonality of the internet and the modern art world, and meaning. She envisions pretty clearly - though admittedly with some blank spaces - a world beyond logic: happy, loving, but without all the problems we inherit by believing in science and mathematics.

As long as I'm rapping on attractive California artists who will never know my name, let me mention Audrey Kawasaki, who makes paintings like Mucha but a little updated for the present.

http://www.audrey-kawasaki.com/

Check out this video where she demonstrates the industrial production process of making buttons:

http://www.vbs.tv/video.php?id=1454975012

After seeing this and falling in love with her, I went to her website and found out that she is way too accomplished and productive to pay attention to me. But that's good - it means I can analyze without fear of finding out I didn't do enough research and am completely wrong.

Beyond her excellent production values, notice that she presents within an altered reality, which she unabashedly creates with arbitrary ignorance of object permanence, the impersonality of the internet and the modern art world, and meaning. She envisions pretty clearly - though admittedly with some blank spaces - a world beyond logic: happy, loving, but without all the problems we inherit by believing in science and mathematics.

As long as I'm rapping on attractive California artists who will never know my name, let me mention Audrey Kawasaki, who makes paintings like Mucha but a little updated for the present.

http://www.audrey-kawasaki.com/

Sunday, March 23, 2008

Government Structure

Reading "Sciences of the Artificial" by Herbert Simon a few weeks ago, I was struck by his distinction between normative and descriptive computer models. Basically, normative models explain how things should be, as when we say, "Governments provide the greatest good for the greatest number," in contrast to a descriptive model which would say something like, "Most governments throughout history have been corrupt and have carried out the oppression of the masses."

His point about computer models is that the normative, simplified, idealized sort are easier to make because it's often difficult to find mathematics to describe the very weird and complex things that can happen in reality. But, of course, descriptive models represent reality better and thus - if the logic is sufficiently deeply structured - they are better able to predict the future.

In my mind, any bureaucracy or corporation has the same abstract structure as a computer program, and thus they can also be considered to be models of human behavior. The major difference is that what is written in a corporate charter, the mission statement of an NGO, or the constitution of a country is signed onto and agreed to by a bunch of people, and these people will call the police and put somebody in jail if they don't behave in accordance with the model. We don't tend to punish natural phenomena when they don't abide by Newton's or Einstein's laws (except by ignoring them), and if the stock market doesn't obey the predictions of some wall street quant's models, then it's the model that is considered defective.

This distinction that I see humans as a whole making rests on the understanding that humans are different and separate from nature. If we move towards breaking down that distinction, it brings up the possibility of making our government charters more descriptive, rather than some idealized story about the way things should be. The group who wrote the US Constitution took a large step in this direction by realizing that every individual will tend to seek more power, and then pitting them against each other with checks and balances.

If we look at the US Government today, the largest aspects that aren't accounted for by the Constitution are the lobbyists and the costs of the election process. Without getting too much into how these processes are inefficient, immoral, or whatever, I'd like to merely propose the academic question: what would a more descriptive Constitution look like?

The essential function of lobbyists is to bring information to Congress and to help it form legislation that will help certain groups do their jobs. If the lobbyist is representing a mining company, he or she will probably skew things in ways most individuals find terrifying: increasing the amount of Chromium 6 intake considered to be "healthy," lowering corporate taxes, etc. But if the lobbyist is working on behalf of GreenPeace, most individuals will benefit from a peaceful sense that nature will still be there when next time we get a vacation in 2026 to go stare at it for a couple weeks. When they're working for large, wealthy individuals or organizations, lobbyists also give Congress lots of money.

Essentially, working this into the Constitution would essentially involve a major expansion of the Congressional Research Service. The public policy research arm of the US Congress, its budget last year was about $90 million, compared with approximately $2.8 billion spent on lobbying. Even without adding in normative features like ensuring that somebody is lobbying for public interests, and even if we include currently hidden features like expensive lunches, junkets, and bags of money that indubitably get exchanged, putting this whole process into law would make it obvious to everyone how to come to Washington and participate in the policy debate.

Similarly, codifying the electoral process might carve into stone some pretty annoying and destructive practices, but once they are in stone we can see them clearly and see better whether a candidates act evil because of their personality or because they are simply being warped by the process.

His point about computer models is that the normative, simplified, idealized sort are easier to make because it's often difficult to find mathematics to describe the very weird and complex things that can happen in reality. But, of course, descriptive models represent reality better and thus - if the logic is sufficiently deeply structured - they are better able to predict the future.

In my mind, any bureaucracy or corporation has the same abstract structure as a computer program, and thus they can also be considered to be models of human behavior. The major difference is that what is written in a corporate charter, the mission statement of an NGO, or the constitution of a country is signed onto and agreed to by a bunch of people, and these people will call the police and put somebody in jail if they don't behave in accordance with the model. We don't tend to punish natural phenomena when they don't abide by Newton's or Einstein's laws (except by ignoring them), and if the stock market doesn't obey the predictions of some wall street quant's models, then it's the model that is considered defective.

This distinction that I see humans as a whole making rests on the understanding that humans are different and separate from nature. If we move towards breaking down that distinction, it brings up the possibility of making our government charters more descriptive, rather than some idealized story about the way things should be. The group who wrote the US Constitution took a large step in this direction by realizing that every individual will tend to seek more power, and then pitting them against each other with checks and balances.

If we look at the US Government today, the largest aspects that aren't accounted for by the Constitution are the lobbyists and the costs of the election process. Without getting too much into how these processes are inefficient, immoral, or whatever, I'd like to merely propose the academic question: what would a more descriptive Constitution look like?

The essential function of lobbyists is to bring information to Congress and to help it form legislation that will help certain groups do their jobs. If the lobbyist is representing a mining company, he or she will probably skew things in ways most individuals find terrifying: increasing the amount of Chromium 6 intake considered to be "healthy," lowering corporate taxes, etc. But if the lobbyist is working on behalf of GreenPeace, most individuals will benefit from a peaceful sense that nature will still be there when next time we get a vacation in 2026 to go stare at it for a couple weeks. When they're working for large, wealthy individuals or organizations, lobbyists also give Congress lots of money.

Essentially, working this into the Constitution would essentially involve a major expansion of the Congressional Research Service. The public policy research arm of the US Congress, its budget last year was about $90 million, compared with approximately $2.8 billion spent on lobbying. Even without adding in normative features like ensuring that somebody is lobbying for public interests, and even if we include currently hidden features like expensive lunches, junkets, and bags of money that indubitably get exchanged, putting this whole process into law would make it obvious to everyone how to come to Washington and participate in the policy debate.

Similarly, codifying the electoral process might carve into stone some pretty annoying and destructive practices, but once they are in stone we can see them clearly and see better whether a candidates act evil because of their personality or because they are simply being warped by the process.

Saturday, March 22, 2008

Welcome to the New Blog

I went to NYC for spring break this week. I love Manhattan because all over the place there is a level of style and quality that is difficult to come by outside of a global metropolis. Moving on from MySpace blogging is another step for me towards participating in the conversation about what that style and quality is, and what it is becoming. Thanks for reading, and please leave me comments so we can start this conversation in earnest. Here's a rundown of the most interesting stuff I saw: |

|

The MOMA has a beautiful new building but the museum is too successful and is unbearably crowded, even on a Wednesday. The show Design and the Elastic Mind is intriguing, but I didn't like the overall scheme of mixing together silly, absurdist ideas with serious, well-thought-out inventions. |

|

| The Muji store on lower Broadway is a little cheaper than the paper-goods-only display in the MOMA store, but really it was worth the extra effort to see it just to learn that Muji makes everything for the home. I've heard it described as the Japanese IKEA, which is entirely accurate as they carry everything from forks to beds to clothes and shoes. What's really amazing is that they fit it into a space smaller than an IKEA lobby. |

|

The best part of the Whitney Biennial was an annex a few blocks from the museum in the old Park Avenue Armory. This immense building, whose drill hall is one of the largest unobstructed enclosed spaces in all of Manhattan, was decorated by Louis Comfort Tiffanny around 1901 and has the air of a stately, venerated gentleman's club. There are small brass signs over the doorways that give the rooms name such as "Board of Officers' Room" and "Company Room G." While the art was pretty good, it was the beautifully haunting deterioration of the building which really took me in. Although all the fixtures and wall-coverings seem to be present, the place hasn't been maintained in decades and is falling apart. It is the most spectacularly engaging built environment I've seen outside a video game. |

|

Walking to an art show in SOHO I chanced to pass by PapaBubble (papabubble.com) and got to taste some hard candy still soft and hot, fresh from - well, I didn't see that part of the process, and I really have no idea how it got to that point. I watched these two craftspeople roll the taffy-like substance into bars and then stick those together to form an image. Later they'll cut it into short chunks. This whole process is exactly like making millifore in glass. I couldn't justify the $7.50 for a bag of candy, but I took these free samples to photograph for you and they are really tasty. |

|

| The Guggenheim is under repair again. Frank Lloyd Wright did some amazing things, but his work was not often executed at the highest level of crafstmanship. I only hope that someone will value some of my work enough to spend millions and millions of dollars to preserve it. |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)